Just waiting to be asked.

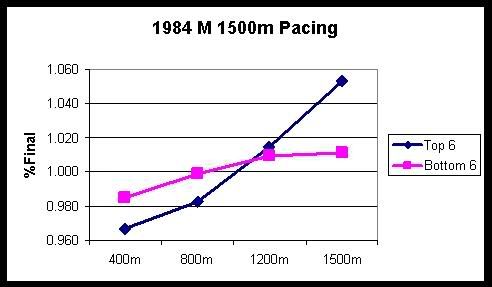

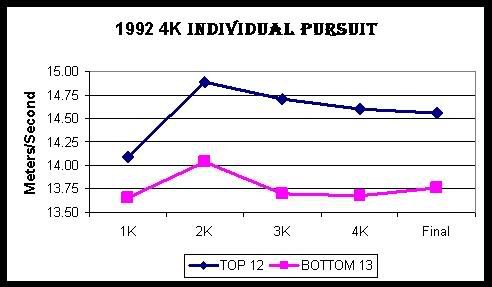

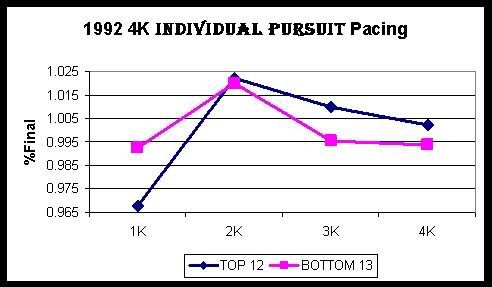

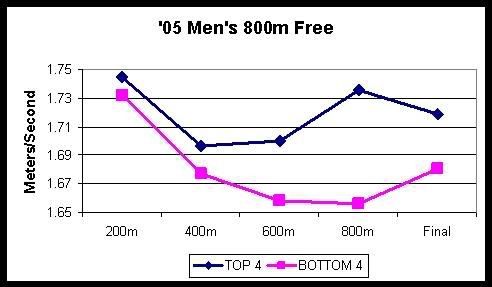

To summarize my basic premise, I’m saying that for middle-distance events that require substantial energy from both aerobic and anaerobic sources (such as 2000m rowing or other events that last roughly 3 ½ - 8 minutes), the most effective pacing strategy is to complete the first portion of the race at a pace that is no faster than the final average pace. In other words, negative-splitting is more effective than otherwise. Furthermore, the positive-split or “fly-and-die” approach will have negative consequences in proportion to how far beyond average pace the initial portion is completed. The physiological rationale is as follows. Performance is affected by energy production (more is better; a positive effect) and fatiguing byproducts of metabolism (K+, H+, NH3, etc.; these have a negative effect). The key to optimal performance is to use a pacing strategy that maximizes energy production while keeping fatiguing agents within tolerable limits. Too much initial intensity disproportionately accelerates the fatigue process to the extent that energy production in the latter portion of the race becomes severely compromised.

I know the benefits of pacing not only from my own extensive racing experience, but from working with and charting the performances of hundreds of athletes over the past several years. Collegiate athletes typically do three 6K and three 2K tests per season. By working with some athletes for two, three, or four years, I have been able to see some individuals perform more than twenty tests over their careers while noting such things as the training they did preceding the tests and

the pacing strategy they used during the tests. Well, guess what – the vast majority have performed better when negative-splitting or at least being more conservative at the start. While I am talking specifically about indoor ergometer tests here, the same phenomenon applies to races on the water.

A couple months ago I was reviewing some published literature on Pacing Strategies:

Code: Select all

Sandals, 2006: “Influence Of Pacing Strategy On Oxygen Uptake

During Treadmill Middle-Distance Running"

International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 27, pp. 37-42

Albertus, 2005: “Effect Of Distance Feedback On Pacing Strategy

and Perceived Exertion During Cycling”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 37, pp. 461-468

Foster, 2005: “Regulation Of Energy Expenditure During Prolonged

Athletic Competition”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 37, pp. 670-675

Garland, 2005: “An Analysis Of the Pacing Strategy Adopted By Elite

Competitors In 2000m Rowing”

British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 39, pp. 39-42

Rauch, 2005: “A Signalling Role For Muscle Glycogen In the Regulation Of Pace During Prolonged Exercise”

British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 39, pp. 34-38

Ansley, 2004: “Anticipatory Pacing Strategies During Supramaximal Exercise Lasting Longer Than 30s”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 36, pp. 309-314

Ansley, 2004: “Regulation Of Pacing Strategies During Successive 4-km Time Trials”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 36, pp. 1819-1825

Foster, 2004: “Effect Of Competitive Distance On Energy Expenditure During Simulated Competition”

International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 25, pp. 198-204

Hill, 2004: “The Relationship Between Power and Time To Fatigue In Cycle Ergometer Exercise”

International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 25, pp. 357-361

Foster, 2003: “Pattern Of Energy Expenditure During Simulated Competition”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 35, pp. 826-831

Thompson, 2003: “The Effect Of Even, Positive and Negative Pacing On

Metabolic, Kinematic and Temporal Variables During Breaststroke Swimming”

European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 88, pp. 438-443

Bishop, 2002: “The Influence Of Pacing Strategy On VO2 and Supramaximal Kayak Performance”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 34, pp. 1041-1047

Jones, 2002: “Bioenergetic Constraints On Tactical Decision Making In Middle Distance Running”

British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 36, pp. 102-104

Leveque, 2002: “Effect Of Paddling Cadence On Time To Exhaustion and

VO2 Kinetics At the Intensity Associated With VO2max In Elite White-Water Kayakers”

Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 27, pp. 602-611

Billat, 2001: “Effect Of Free Versus Constant Pace On Performance and Oxygen Kinetics In Running”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 33, pp. 2082-2088

Fukuba, 1999: “A Metabolic Limit On the Ability To Make Up For Lost Time In Endurance Events”

Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 87, pp. 853-861

Liedl, 1999: “Physiological Effects of Constant Versus Variable Power During Endurance Cycling”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 31, pp. 1472-1477

Palmer, 1999: “Metabolic and Performance Responses To Constant-Load

Vs. Variable-Intensity Exercise In Trained Cyclists”

Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 87, pp. 1186-1196

Palmer, 1997: “Effects Of Steady-State Versus Stochastic Exercise On Subsequent Cycling Performance”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 29, pp. 684-687

Craig, 1995: “Influence Of Test Duration and Event Specificity On Maximal Accumulated Oxygen Deficit

Of High Performance Track Cyclists”

International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 16, pp. 534-540

Foster, 1994: “Pacing Strategy and Athletic Performance”

Sports Medicine, vol. 17, pp. 77-85

Foster, 1993: “Effect of Pacing Strategy On Cycle Time Trial Performance”

Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, vol. 25, pp. 383-388

Ariyoshi, 1979: “Influence Of Running Pace Upon Performance:

Effects Upon Treadmill Endurance Time and Oxygen Cost”

European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 41, pp. 83-91

Robinson, 1958: “Influence Of Fatigue On the Efficiency Of Men During Exhausting Runs”

Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 12, pp. 197-201

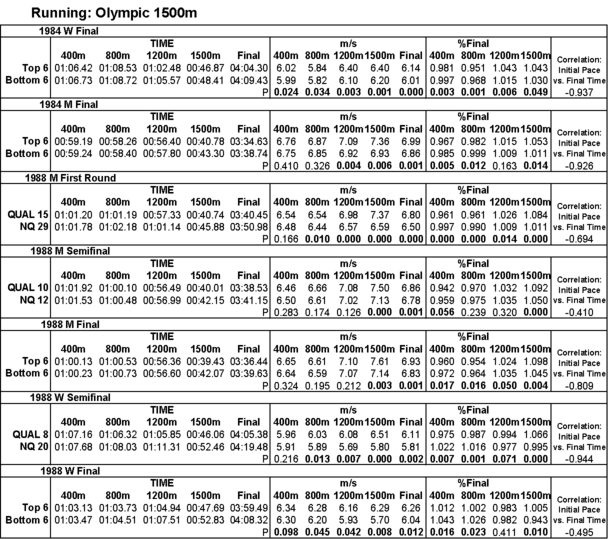

In particular, the article by Garland got me thinking. Garland looked at OTW results for HW men & women from the 2000 Olympics and 2001 & 2002 World Championships. He used the format of determining final average speed and calculating each 500m segment as a percentage of the final to determine pacing strategy. Garland concluded there was no significant difference in the pacing strategies used by “winners” vs. “losers”. However, his study utilized preliminary heats as well as finals. He excluded races where competitors appeared not to be giving maximal effort (such as crews that shut down in a qualifying heat), but this was somewhat subjective. Garland also looked at results from the British Indoor Rowing Championship for 2001 & 2002 and again concluded there was no difference between “winners” and “losers”. Not much information was provided about this analysis, except that Garland used time rather than Watts for comparison. Here are a couple of comments from Garland’s paper: “The data presented in this paper do not fully express the magnitude of the increased effort and increased physiological load at the start of the [OTW] race, because only times and speeds are recorded, rather than power output—a superior index of physiological load. The first 500 m section was the fastest despite the inclusion of the initial acceleration from a stationary start. It requires a much higher average power output to complete the first 500 m in 100 seconds, for example, than it does to complete the second 500 m in 100 seconds. …Power outputs to accelerate the boat from standing to race pace are as high as 700 W compared with 350–500 W later on in the race. These additional considerations make the adoption of a fast start strategy even more remarkable.” And: “It should be noted that this study has only shown the self selected pacing strategy used by rowers, but has not necessarily shown the physiologically optimal pacing strategy, nor provided physiological evidence as to why the first 500 m sector is rowed faster than the other sectors.”

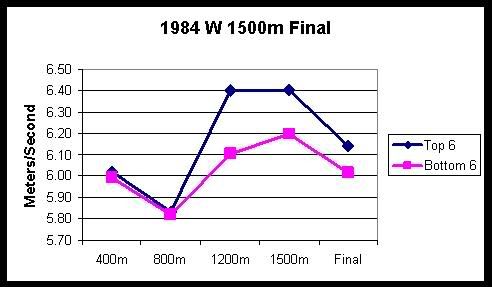

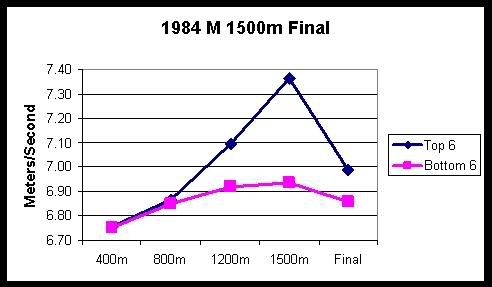

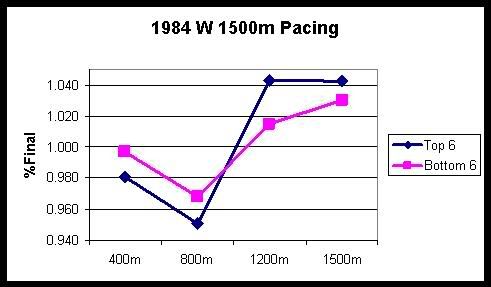

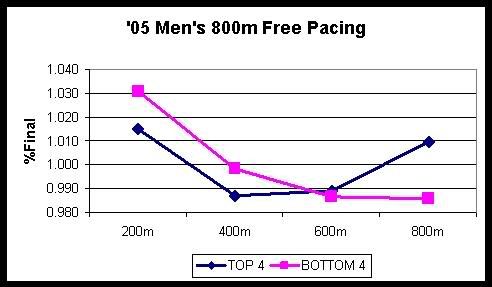

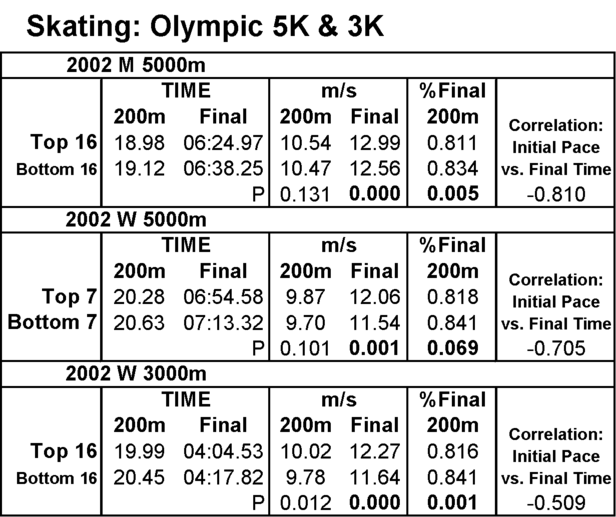

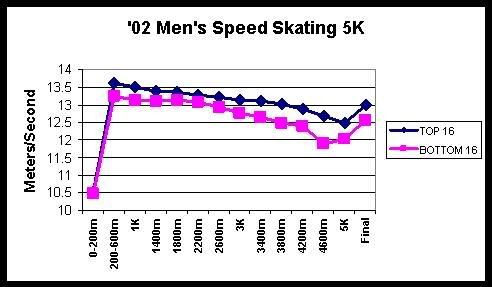

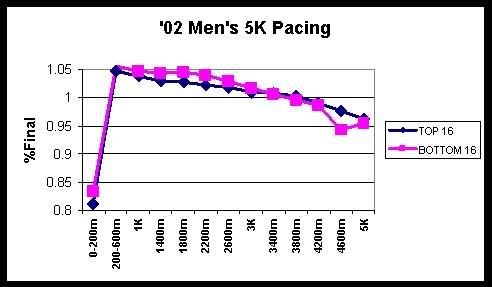

I wondered if I could find data to replicate Garland’s approach. I decided to look not only for rowing results but also results from other sports such as running, swimming, cycling, and skating. I was only able to get complete pacing breakdowns for other sports from select years, but what I’ve been able to get has been very useful. I’ve been able to find pretty much all the results from rowing that I could want, with only a few gaps here and there. For OTW rowing, I wanted more data than Garland used for greater statistical power. I also decided to only use results from A-Finals to eliminate as much as possible any concerns about athlete motivation. For indoor rowing, I converted all pace times from seconds to Watts for analysis. Everything I have looked at so far has confirmed my initial hypothesis: faster athletes start their races more conservatively than slower athletes. This can be seen even within the limited confines of an Olympic final.

I gathered results from Olympic running, cycling, and skating at

http://www.aafla.org/search/search.htm;

Olympic & WC swimming at

http://www.fina.org/main/results/results.htm ;

Olympic & WC rowing at

http://www.fisa.org/results/default.sps ;

and indoor rowing at

http://www.concept2.co.uk/wirc/results.php .

Besides illustrating my major thesis, a few other interesting things have come to light which I will point out as I find time to show my results. Hopefully I’ll get some results posted in the next day or two.

Mike Caviston