tbowles wrote:

I keep blowing up in my time-trial efforts ... I even managed to blow up at a 500m (had to stop at 350m,as I'd started all out), not to mention 1000m, and 2000m.

My question is how all of you more experienced rowers have 'figured out' how to race ... I understand running pacing and understanding listening to my body, but I am embarrassed by my "DNFs" at such short TT efforts. I can't get over how comfortable a pace can feel for 500-600-700m and then all of the sudden the wheels just come off! Is this as simple as just 'slowing down' and trial-and-error, or are there some 'benchmark' workouts I should be doing to help with pacing?

Any tips at all would be appreciated!

Sounds like you're starting too fast, you wouldn't do it in a running race so don't do it on the erg either!

Here's an article by a top coach (Mike Caviston if you want to look him up), hope it helps;

"Fly-and-die is just not a smart way to approach a race. It is usually employed by athletes who are inexperienced, who don’t have a realistic sense of their current abilities, or who allow themselves to be overwhelmed by the excitement of competition. The physiological consequence is to accelerate the accumulation of fatiguing metabolic byproducts of intense muscular contraction (LACT, NH3, K+, etc.), resulting in severe discomfort and the inability to hold the desired pace

The idea that there are “free” strokes anywhere in a 2K is a common misconception among the rowing community. Anyone with even a rudimentary understanding of physics and thermodynamics should recognize this is impossible. Starting a race with several intense, sub-race-pace strokes will probably utilize the muscles’ ready supply of phosphagens (ATP & phosphocreatine).

Some people figure, what does it matter when I use my phosphagen stores? It’s anaerobic anyway, so I may as well use them at the start of the race to get a good position in the first 500m, rather than use them to sprint at the end. This thinking is incorrect. After a few seconds (when phosphagen stores are depleted) the muscles support intense contractions by rapidly breaking down glycogen into pyruvate. This rapid or “anaerobic” glycolysis results in the release of hydrogen ions (H+) that must be buffered, resulting in the formation of lactate, and the resulting decrease in muscle pH is a contributing factor to fatigue.

So far I’m sure everyone is nodding their head saying, “Uh-huh, I know that, so what?” The “so what” is that the rapidity of glycolysis is accelerated by the feed-forward signals resulting from the overly-intense, sub-race-pace strokes that start the race. In other words, if you plan to race at a 1:40 pace and take off at a 1:27 pace, your muscles don’t know that you intend to slow up in a few strokes. They immediately jump into action and rapidly break down glycogen to liberate as much immediate energy as possible, and the signal doesn’t immediately stop when you settle into your planned race pace.

The result is a much greater initial rise in lactate. Furthermore, phosphagen compounds help buffer decreasing muscle pH, so it is ill-advised to deplete them early. I don’t know about you, but racing for me is tough enough already without dragging the albatross of increased lactate accumulation into the second 500m, so I prefer to start more conservatively.

Now, some coaches will encourage a young/inexperienced athlete to start hard with the hope that they will discover some hidden gear and perform at a level they didn’t think was possible. Unfortunately, a likely result is the athlete will have such an unpleasant experience that they develop a mental block against racing hard, and it may be a long, long time before they reach their true potential.

The even-split approach to racing makes the most sense from a purely mechanical standpoint. Consider the hypothetical example of covering 2000m with an average pace of 1:36 either by holding a steady 1:36 pace for the entire distance, or covering half with a 1:35 pace and half with a 1:37 pace. Either method would result in a 6:24 2K, but because of the cubic relationship between velocity and power, and the proportionately greater energy cost of the 1:35 pace, more total energy is expended with the uneven pace. If an athlete is truly performing at maximum capacity, the less efficient pacing results in a slower time.

If you actually calculate the energy difference with this hypothetical example, you might be tempted to say the difference is pretty trivial, but I say even a fraction of a second is significant. And the greater the variation in pace during the race, the greater the amount of energy lost. So logically it must be concluded that the most effective race strategy would be to hold an even pace from start to finish.

But I don’t race that way. I prefer to start at a pace slower than my overall goal pace. But it’s also important to recognize that any strokes slower than your true potential represent lost time that can never be made up, no matter how fast you row later in the race. So you can’t take it too easy either, and that presents a real quandary. On the one hand, you risk going too hard and burning out too soon, and on the other you risk getting too far behind your optimal pace. It’s a fine line to tread, but with enough training and racing experience as well as a little common sense, I think anyone can create an effective race strategy.

I think the optimal pacing strategy for a 2K race is pretty close to:

800m (40%) @ GP +1; 600m (30%) @ GP; 400m (20%) @ GP – 1; and 200m (10%) @ GP – 2. [GP = Goal Pace, so to row 2K in 6:24, row the first 800m @ 1:37, the next 600m @ 1:36, the next 400m @ 1:35, and the final 200m @ 1:34.]"

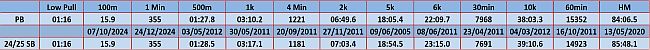

67 year old, 72 kilo (159lbs), 5'8''/174cm (always the shortest on the podium!) male. Based just south of London.

Best rows as an over 60. One Hour.....16011 metres. 30 mins.....8215 metres. 100k 7hrs 14 mins.